Tuesday, August 31, 2010

The effect of clouds on climate: A key mystery for researchers | Energy Bulletin

Hermaphroditic frogs, hip-hop science & corporate culture

In 1997 UC Berkley endocrinologist Tyrone Hayes was contracted by a subsidiary of Syngenta corporation to do research on the widely used agricultural chemical atrazine. Not surprisingly, the company wasn't pleased when Hayes concluded that the chemical might affect male reproductive development in frogs. Prevented by the terms of the contract from publishing the results, Hayes waited for the contract to expire, repeated an expanded version of the research he had done under contract and published the results. Thus began what has become a decade long battle between Hayes and Syngenta.

In 1997 UC Berkley endocrinologist Tyrone Hayes was contracted by a subsidiary of Syngenta corporation to do research on the widely used agricultural chemical atrazine. Not surprisingly, the company wasn't pleased when Hayes concluded that the chemical might affect male reproductive development in frogs. Prevented by the terms of the contract from publishing the results, Hayes waited for the contract to expire, repeated an expanded version of the research he had done under contract and published the results. Thus began what has become a decade long battle between Hayes and Syngenta.Hayes, who has always admitted to wearing two hats -- that of objective scientist and that of impassioned activist -- has long been recognized as a character. As in the clip below, he frequently peppers his academic talks with a rap delivery.

It turns out, however, that his hip-hop style has a bit of a gangsta flavor. For years Hayes has been sending rap emails with what is being described as lewd and inappropriate comments to various Syngenta employees. Now, in an attempt to discredit Hayes and his research, Syngenta has released the documents and actively worked to construct an ethical controversy.

Atrazine has been banned in the EU and, with the EPA re-re-restudying its allow-ability in the US, Syngenta seems to have shot off both barrels; attacking both Hayes and his research. It seems that the blood sport of American politics is beginning to affect its science as well.

For those interested in more, a brief clip of an academic talk by Hayes is below and here are links to the legal complaint against Hayes, the emails he sent, articles questioning the ethics of his actions in Nature and Science, and an article outlining the early history of the relationship between Hayes and Syngenta (which dates back to 1997) can be found here.

Saturday, August 28, 2010

Burtynsky goes to the Gulf

Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky, who took the photo of the LA freeway system at the top of the right hand column and several others on the blog, has a new series of photos of the Gulf oil spill. The series, executed in large-scale digital c-prints, was captured this May and June when Burtynsky boarded a helicopter and took aerial shots of the burning Deepwater Horizon rig where the crisis — the worst marine oil spill in history — originated. An artist whose work has long been driven by deep-seated environmental concerns, Burtynsky's photos can be seen on the website of Toronto’s Nicholas Metivier Gallery (a preview of the exhibition opening on September 16).

Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky, who took the photo of the LA freeway system at the top of the right hand column and several others on the blog, has a new series of photos of the Gulf oil spill. The series, executed in large-scale digital c-prints, was captured this May and June when Burtynsky boarded a helicopter and took aerial shots of the burning Deepwater Horizon rig where the crisis — the worst marine oil spill in history — originated. An artist whose work has long been driven by deep-seated environmental concerns, Burtynsky's photos can be seen on the website of Toronto’s Nicholas Metivier Gallery (a preview of the exhibition opening on September 16). Burtynsky has explored the theme of oil for more than a decade, from the Alberta oil sands to Baku, Azerbaijan, one of the earliest sites of oil discovery. These images are gathered in the book Burtynsky: Oil, and a previous blog about the Oil series, with links, is here. The show’s curator, Paul Roth writes in the accompanying book: “The subject is not oil. In these pictures, Edward Burtynsky shows the man-made world—the human ecosystem—that has risen up around the production, use, and dwindling availability of our paramount energy source.”

Burtynsky has explored the theme of oil for more than a decade, from the Alberta oil sands to Baku, Azerbaijan, one of the earliest sites of oil discovery. These images are gathered in the book Burtynsky: Oil, and a previous blog about the Oil series, with links, is here. The show’s curator, Paul Roth writes in the accompanying book: “The subject is not oil. In these pictures, Edward Burtynsky shows the man-made world—the human ecosystem—that has risen up around the production, use, and dwindling availability of our paramount energy source.”

Thursday, August 26, 2010

Bad news about coal ..... and future climate policy.

Coal fired power plants, like the Scherer plant in Georgia shown above, are notable for several reasons. First, they currently provide roughly 50% of US electricity. Second, coal is a comparatively plentiful fossil fuel and, despite projected cost increases, remains comparatively cheap. Third, power plants are massive sources of atmospheric carbon dioxide: according to data from CARMA, the 8,000 power plants in the US are responsible for roughly one-sixteenth of the world's carbon dioxide emissions. But not all power plants are created equal. Nuclear plants have minimal emissions while the twelve largest carbon emitters (of which Scherer is the largest) are all coal fired plants (emitting between 17 and 25 million tons of C02 annually).

New power plants cost billions to construct and operate for decades. Thus, in a rational world, carbon emissions would be a significant consideration when constructing new plants. And, since it is widely recognized that large scale deployment of 'clean coal' technology is 15-20 years away, one would think that power companies would be shying away from the construction of new coal fired plants. But, as a recent review of documents by AP has shown, this isn't the case.

An Associated Press examination of U.S. Department of Energy records and information provided by utilities and trade groups shows that more than 30 traditional coal plants have been built since 2008 or are under construction.

The expansion, the industry's largest in two decades, represents an acknowledgment that highly touted "clean coal" technology is still a long ways from becoming a reality and underscores a renewed confidence among utilities that proposals to regulate carbon emissions will fail. The Senate last month scrapped the leading bill to curb carbon emissions following opposition from Republicans and coal-state Democrats.

"Building a coal-fired power plant today is betting that we are not going to put a serious financial cost on emitting carbon dioxide," said Severin Borenstein, director of the Energy Institute at the University of California-Berkeley. "That may be true, but unless most of the scientists are way off the mark, that's pretty bad public policy."

Federal officials have long struggled to balance coal's hidden costs against its more conspicuous role in providing half the nation's electricity.

Hoping for a technological solution, the Obama administration devoted $3.4 billion in stimulus spending to foster "clean-coal" plants that can capture and store greenhouse gases. Yet new investments in traditional coal plants total at least 10 times that amount — more than $35 billion.

Approval of the plants has come from state and federal agencies that do not factor in emissions of carbon dioxide, considered the leading culprit behind global warming. Scientists and environmentalists have tried to stop the coal rush with some success, turning back dozens of plants through lawsuits and other legal challenges.

As a result, current construction is far more modest than projected a few years ago when 151 new plants were forecast by federal regulators. But analysts say the projects that prevailed are more than enough to ensure coal's continued dominance in the power industry for years to come.

Sixteen large plants have fired up since 2008 and 16 more are under construction, according to records examined by the AP.

Combined, they will produce an estimated 17,900 megawatts of electricity, sufficient to power up to 15.6 million homes — roughly the number of homes in California and Arizona combined.

They also will generate about 125 million tons of greenhouse gases annually, according to emissions figures from utilities and the Center for Global Development. That's the equivalent of putting 22 million additional automobiles on the road.

The new plants do not capture carbon dioxide. That's despite the stimulus spending and an additional $687 million spent by the Department of Energy on clean coal programs.

While the news itself is troubling, it is what this news implies about the future of US climate change policy that is truly disturbing. As anyone who has followed the comments of talking heads about the current unemployment situation knows, uncertainty kills investment. This isn't simply a talking point, there is empirical economic research documenting the connection. Thus, the paradox: In the wake of the collapse at Copenhagen, conventional wisdom renders the future of climate negotiations uncertain, a business environment that, typically would lead firms to delay major infrastructure investment.

But this is not what the power companies have done. Instead, they have massively increased their commitment to coal. There seems, to me, to be only two possible explanations. 1) These guys are collectively stupid and betting billions on an uncertain regulatory future or 2)they know they have enough politicians under their control that there is no serious likelihood of future regulatory change that would undermine their investment in coal. My bet is on the second.

Update:

No sooner had I finished this post, than I came across an article by George Monbiot. He discusses lots of interesting political developments that are worth knowing about and I've linked to the referenced version of the piece. Here is the concluding paragraph, which largely echos my conclusion:

Yes, man-made climate change denial is about politics, but it’s more pragmatic than ideological. The politics have been shaped around the demands of industrial lobby groups, which happen, in many cases, to fund those who articulate them. Right-wingers are making monkeys of themselves over climate change not just because their beliefs take precedence over the evidence, but also because their interests take precedence over their beliefs.

Tuesday, August 24, 2010

Ellen Dunham-Jones: Retrofitting Suburbia

Good news about plastic, sort of ....

Global plastic production has risen nearly 6-fold since 1980.

Global plastic production has risen nearly 6-fold since 1980.There has been a lot of focus on both the length of time it takes plastics to break down and their tendency to accumulate in the ocean (particularly the 'Great Pacific Garbage Patch'). Brought together by ocean currents known as gyres, the plastics have dramatically detrimental consequences for ocean birds.

Recently, there have been a couple of studies shedding new (and, perhaps, hopeful) news about plastics. First, there is evidence that plastic breaks down in the ocean much faster than previously believed. On the down side, the breakdown tends to release potentially toxic chemicals like Bisphenol_A which Health Canada has declared as hazardous to human health.

Second, the current issue of Science reports the result of a 22 year study of the accumulation of plastic in the less publicized 'Atlantic gyre' (see illustration).

Second, the current issue of Science reports the result of a 22 year study of the accumulation of plastic in the less publicized 'Atlantic gyre' (see illustration).One surprising finding is that the concentration of floating plastic debris has not increased during the 22-year period of the study, despite the fact that the plastic disposal has increased substantially. The whereabouts of the "missing plastic" is unknown.

.....

A companion study published in Marine Pollution Bulletin details the characteristics of the plastic debris collected in these tows. Most of the plastic is millimeters in size and consists of polyethylene or polypropylene, materials that float in seawater. There is evidence that biological growth may alter the physical characteristics of the plastic over time, perhaps causing it to sink.

Thus, like the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, this may be more a case of out-of-sight out-of-mind, than a real good news story.

The full report is available here: Kara Lavender Law, Skye Moret-Ferguson, Nikolai A. Maximenko, Giora Proskurowski, Emily E. Peacock, Jan Hafner, and Christopher M. Reddy. Plastic Accumulation in the North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre. Science, 2010; DOI: 10.1126/science.1192321

Monday, August 23, 2010

Giant BP Oil Plume At Bottom of Gulf of Mexico

Sunday, August 22, 2010

Friday, August 20, 2010

The Epistemology of Archaeology

Pakistan, Russia and Sasakatchewan

Wednesday, August 18, 2010

Artificial meat by 2050?

These are some of the more striking conclusions reported by a set of high level UK academics in the current issue of The Royal Society's Philosophical Transactions B which is devoted to 21 papers dealing with the topic of Food Security: Feeding the World in 2050. Among the topics are the following:

• Dimensions of global population projections: what do we know about future population trends and structures?

• Food consumption trends and drivers

• Urbanization and its implications for food and farming

• Income distribution trends and future food demand

• Possible changes to arable crop yields by 2050

• Livestock production: recent trends, future prospects

• Trends and future prospects for Marine and Inland capture fisheries

• Competition for land, water and ecosystem services

• Implications of climate change for agricultural productivity in the early twenty-first century

• Globalization's effects on world agricultural trade, 1960–2050

• Agricultural R&D, technology and productivity

• Food waste within food supply chains: quantification and potential for change to 2050

..... and a number of others

Taken together the papers provide a exceptionally thorough look at the future of food supply.

While the scale of the problem, increasing food supply by 70% in the next 40 years, is daunting, the researchers don't see it as insurmountable. The papers identify a number of potential avenues to increase supply. Moreover, as with the current energy debate, there is likely to be a struggle between existing agribusiness which will pressure governments for subsidies to increase supply and those who advocate conservation and efficiency (one of the papers suggest that there is 30-40% food waste in both rich and poor countries).

Sunday, August 15, 2010

Community Resilience: Lessons from New Orleans

Robert Cates, one of the authors of Community Resilience: Lessons from New Orleans and Hurricane Katrina, is working on a follow up article that makes explicit a number of general lessons about the creation of resilient communities.

The 8 lessons, listed below, are described in greater detail by Andrew Revkin.

1. The United States is vulnerable to enormous disasters despite being the richest and most powerful nation on earth.

2. Creating community resilience is a long-term process.

3. Surprises should be expected.

4. The best scientific and technological knowledge does not get used or widely disseminated.

5. Major response capability and resources were invisible, refused, or poorly used.

6. Disasters accelerate existing pre-disaster trends.

7. Overall vulnerability to hurricanes has grown from multiple causes.

8. Efforts to provide protection reduced vulnerability to frequent small events but increased vulnerability to rare catastrophic events.

While the work uses the term resilience, it is more in the ordinary language sense than in the technical sense developed by Holling and other resilience science researchers. Conceptually, the analysis is closer to Perrow's treatment of system accidents (see Normal Accidents) than to resilience theory.

Since I've got a chapter "Disasters as System Accidents" in the forthcoming Earthscan Press book Dynamics of Disaster: Lessons on Risk, Response and Recovery that covers some of the same territory, I thought I'd point out the major differences between this analysis and my own.

First, the concept of a system accident refers to an accident resulting from the unanticipated interaction of multiple failures in a complex system. While both Cates and I agree on the importance of multiple causes and the impossibility of perfect foresight (hence, the importance he places on surprises), I have a broader view of the types of causes that should be examined. Cates emphasizes two broad types of factor: natural factors (e.g., hurricane) and technological factors (e.g., levees). The central point of my chapter is the need to incorporate a third type of factor, socio-cultural, into the analysis. I don't think it is possible to fully understand what happened in New Orleans without taking account of both the specific culture of the city and the longstanding history of racism in the region.

Second, Cates argues that disasters accelerate pre-existing trends. Specifically, Katrina accelerated the economic and population decline that New Orleans was already experiencing. While Katrina does appear to have had this effect, I don't think it is safe to generalize from the single case. Naomi Kline, in her book The Shock Doctrine provides a number of examples where natural and human induced disasters alter the situation and provide the opportunity for a dramatic re-organization of the existing state of affairs. These cases illustrate not an acceleration of pre-existing trends but, rather, the replacement of the old trend by a new one. Thus, for example, the tsunami that hit Thailand and wiped out a number of small local villages that had been intractably opposed to tourist development became an opportunity for large corporations to move in and build resorts in those areas.

Third, as the following quote illustrates, Cates clearly understands that there is a potential relationship between adaptation and vulnerability.

A major concern in adapting to climate change is whether successful short-term adaptation may lead to larger long-term vulnerability. This seemed to be the case from the 40 year period between Hurricane Betsy and Katrina, when new and improved levees, drainage pumps, and canals — successfully protected New Orleans against three hurricanes in 1985, 1997, and 1998. But these same works permitted the massive development of previously unprotected areas and the flooding of these areas that resulted when the works themselves failed were the major cause of the Katrina catastrophe.

However, while noting the potential relationship, he doesn't provide any conceptual ideas to help us make sense of it. Individuals familiar with panarchy theory will recognize the similarities between the situation described above and the rigidities present in the conservation phase of the adaptive cycle.

Thursday, August 12, 2010

What do slow boats to China tell us about the future?

According to the Guardian,

According to the Guardian, the world’s largest cargo ships are travelling at lower speeds today than sailing clippers such as the Cutty Sark did more than 130 years ago.

A combination of the recession and growing awareness in the shipping industry about climate change emissions encouraged many ship owners to adopt “slow steaming” to save fuel two years ago. This lowered speeds from the standard 25 knots to 20 knots, but many major companies have now taken this a stage further by adopting “super-slow steaming” at speeds of 12 knots (about 14mph).

Travel times between the US and China, or between Australia and Europe, are now comparable to those of the great age of sail in the 19th century. American clippers reached 14 to 17 knots in the 1850s, with the fastest recording speeds of 22 knots or more.

Maersk, the world's largest shipping line, with more than 600 ships, has adapted its giant marine diesel engines to travel at super-slow speeds without suffering damage. This reduces fuel consumption and greenhouse gas emissions by 30%. It is believed that the company has saved more than £65m on fuel since it began its go-slow.

Ship engines are traditionally profligate and polluting. Designed to run at high speeds, they burn the cheapest "bunker" oil and are not subject to the same air quality rules as cars. In the boom before 2007, the Emma Maersk, one of the world's largest container ships, would burn around 300 tonnes of fuel a day, emitting as much as 1,000 tonnes of CO2 a day – roughly as much as the 30 lowest emitting countries in the world.

Maersk spokesman Bo Cerup-Simonsen said: "The cost benefits are clear. When speed is reduced by 20%, fuel consumption is reduced by 40% per nautical mile. Slow steaming is here to stay. Its introduction has been the most important factor in reducing our CO2 emissions in recent years, and we have not yet realised the full potential. Our goal is to reducing CO2 emissions by 25%."

The article pitches slow steaming as financially beneficial for the shipping companies, environmentally beneficial for the world and "here to stay." I'm not so sure ....

To put the change into context, globalization was the dominant economic trend of the last 40 years. Manufacturing of many types shifted from North America and Europe to various low cost producers in the developing world, but the bulk of that manufacturing was still consumed in Europe and North America.

Containerized shipping emerged as a cost effective way to facilitate the massive growth in transportation of goods that accompanied this economic shift. Wal-Mart, Costco and other stores used high technology to manage inventory and drive down the cost of transportation and storage in order to sell at the lowest possible price. The emergence of big box retail is the flip side of outsourced manufacturing. Driven by the the need for expanded transportation capacity and the retailer's emphasis on just-in-time delivery the shipping industry responded by building larger and faster ships, container rail, etc.

Containerized shipping emerged as a cost effective way to facilitate the massive growth in transportation of goods that accompanied this economic shift. Wal-Mart, Costco and other stores used high technology to manage inventory and drive down the cost of transportation and storage in order to sell at the lowest possible price. The emergence of big box retail is the flip side of outsourced manufacturing. Driven by the the need for expanded transportation capacity and the retailer's emphasis on just-in-time delivery the shipping industry responded by building larger and faster ships, container rail, etc.  Container ships, as shown, have increased in size and capacity. (Capacity is meausred in Twenty-foot Equivalent Units (TEU), that is the number of twenty-foot containers the ship can carry.) PanaMax class ships (ships limited in size by their ability to pass through the Panama Canal), which dominated shipping during the 80's, have been surpassed by the larger Post-PanaMax classes. When the current expansion of the Panama Canal is complete, sixth generation ships from the New PanaMax class will be able to navigate the canal.

Container ships, as shown, have increased in size and capacity. (Capacity is meausred in Twenty-foot Equivalent Units (TEU), that is the number of twenty-foot containers the ship can carry.) PanaMax class ships (ships limited in size by their ability to pass through the Panama Canal), which dominated shipping during the 80's, have been surpassed by the larger Post-PanaMax classes. When the current expansion of the Panama Canal is complete, sixth generation ships from the New PanaMax class will be able to navigate the canal. But ships have not only increased in size (blue line), but also in speed (green line) and carrying capacity (bottom axis). However, while it is possible to get larger ships to meet the speed of earlier ships by increasing the size of the motor (red line), current designs have reached the limits of speed. It is from these maximum designed limits that current shipping speeds have been reduced.

But ships have not only increased in size (blue line), but also in speed (green line) and carrying capacity (bottom axis). However, while it is possible to get larger ships to meet the speed of earlier ships by increasing the size of the motor (red line), current designs have reached the limits of speed. It is from these maximum designed limits that current shipping speeds have been reduced.But the question of whether or not the slow speeds are here to stay hinges on the future of globalization and the nature of the transportation/distribution system that has evolved with it. Stated in resilience theory terms, will the world economy rebound and return to its previous system state? If that is the case, then we would expect slow speeds to be a temporary phenomena. Or, is the current economic slump the leading edge of a global economic transition that de-emphasizes globalization and re-emphasizes localization? If that is the case, then the slow speeds may be here to stay.

I don't claim to know enough to answer the question, but some additional understanding of the economic context is important. Following the banking collapse of 2008 the global economy went into recession and factories slowed production. Without the need for so much capacity, the shipping industry removed a significant number of ships from use and instituted the slow shipping provisions. As the economy has recovered (at least somewhat) the increased demand for shipping has not been met by adding additional ships (i.e., expanded capacity) and, as shown in the chart, the cost of shipping has increased significantly.

I don't claim to know enough to answer the question, but some additional understanding of the economic context is important. Following the banking collapse of 2008 the global economy went into recession and factories slowed production. Without the need for so much capacity, the shipping industry removed a significant number of ships from use and instituted the slow shipping provisions. As the economy has recovered (at least somewhat) the increased demand for shipping has not been met by adding additional ships (i.e., expanded capacity) and, as shown in the chart, the cost of shipping has increased significantly. From what I've been able to tell, the retail end of things has been able to factor in both the additional cost of transportation and information that a particular product is no longer in production/available. What they seem to be up in arms about is the distribution issue -- the product is in production but delayed. Google 'shipping delays' and you will see what I mean. Globalized retailers have built just-in-time delivery into their retail scheme. And not having a product on the shelf is a no no. Telling a customer it will be in by day X and not have it show is even worse. Simply put, whether or not slow shipping stays will be dependent on changes in the retail industry. If the big box model collapses and/or other industries (like consumer electronics) that dependent on just-in-time delivery can adapt to slower delivery times, then slow shipping will remain. If, however, the global economic system turns out to be resilient and things return to the way they were, I suspect the pressure for speeded up delivery will be too great for the shipping industry to ignore.

Tuesday, August 10, 2010

When the animals strike back

.... or maybe 'stealing' isn't the best way to describe what the deer is up to.

Sunday, August 8, 2010

In Defense of Difference

Experts have long recognized the perils of biological and cultural extinctions. But they’ve only just begun to see them as different facets of the same phenomenon, and to tease out the myriad ways in which social and natural systems interact. Catalyzed in part by the urgency that climate change has brought to all matters environmental, two progressive movements, incubating already for decades, have recently emerged into fuller view. Joining natural and social scientists from a wide range of disciplines and policy arenas, these initiatives are today working to connect the dots between ethnosphere and biosphere in a way that is rapidly leaving behind old unilateral approaches to conservation. Efforts to stanch extinctions of linguistic, cultural, and biological life have yielded a “biocultural” perspective that integrates the three. Efforts to understand the value of diversity in a complex systems framework have matured into a science of “resilience.” On parallel paths, though with different emphases, different lexicons, and only slightly overlapping clouds of experts, these emergent paradigms have created space for a fresh struggle with the tough questions: What kinds of diversity must we consider, and how do we measure them on local, regional, and global scales? Can diversity be buffered against the streamlining pressures of economic growth? How much diversity is enough? From a recent biocultural diversity symposium in New York City to the first ever global discussion of resilience in Stockholm, these burgeoning movements are joining biologist with anthropologist, scientist with storyteller, in building a new framework to describe how, why, and what to sustain.

....

It’s the ability of a system — whether a tide pool or township — to withstand environmental flux without collapsing into a qualitatively different state that is formally defined as “resilience.” And that is where diversity enters the equation. The more biologically and culturally variegated a system is, the more buffered, or resilient, it is against disturbance. Take the Caribbean Sea, where a wide variety of fish once kept algae on the coral reef in check. Because of overfishing in recent years, these grazers gradually gave way to sea urchins, which continued to keep algae levels down. Then in 1983 a pathogen moved in and decimated the urchin population, sending the reef into a state of algal dominance. Thus, the loss of diversity through overfishing eroded the resilience of the system, making it vulnerable to an attack it likely could have withstood in the past.

....

“There is an underlying assumption in much of the literature that the world can be saved from these problems that we face — poverty, lack of food, environmental problems — if we bring consumption levels across the world up to the same levels [of] North America and Europe.” But this sort of convergence, says Pretty, would require the resources of six to eight planets. “How can we move from convergence to divergence, and hence diversity?”

Traditional environmentalism, with its tendency to erect impermeable theoretical barriers between nature and culture, between the functions of artificial and natural selection, hasn’t been able to accommodate the perspective necessary to see larger patterns at work. Its distinction — as the writer Lewis Lapham recently put it — “between what is ‘natural’ (the good, the true, the beautiful) and what is ‘artificial’ (wicked, man-made, false)” has obscured their profound interrelatedness. Whether expressed as biocultural diversity or as diverse social-ecological systems, the language of these new paradigms reframes the very concept of “environment.” Explicit in both terms is a core understanding that as human behavior shapes nature in every instant, nature shapes human behavior. Also explicit is that myth, legend, art, literature, and science are not only themselves reflections of the environment, passed through the filter of human cognition, but that they are indeed the very means we have for determining the road ahead.

If you read the whole article you will find that biocultural diversity is, to my mind, too simplistically treated as equivalent to linguistic diversity -- a problem also found in an earlier (and similar) argument made by Thomas Homer-Dixon in We Need a Forest of Tongues. Linguistic diversity isn't important in and of itself but, rather, because it acts as a buffer that slows the homogenization process. If you don't communicate with the dominant group, then you are less likely to be consumed by it. But there are other factors, like the growth of transportation and communication technologies and the economics of globalization, that underpin the homogenization process. The trick is to discover how to be connected without being assimilated.

Friday, August 6, 2010

Summer reruns!

1. The Homogenization of America

2. New Book: William Catton Returns with "Bottleneck"

3. Social and Natural Systems in the Decline of North America's Megafauna

4. The Deep Horizon Fiasco: Fluid dynamics and its Environmental Legacy

5. Neil Adger on Social Resilience

Thursday, August 5, 2010

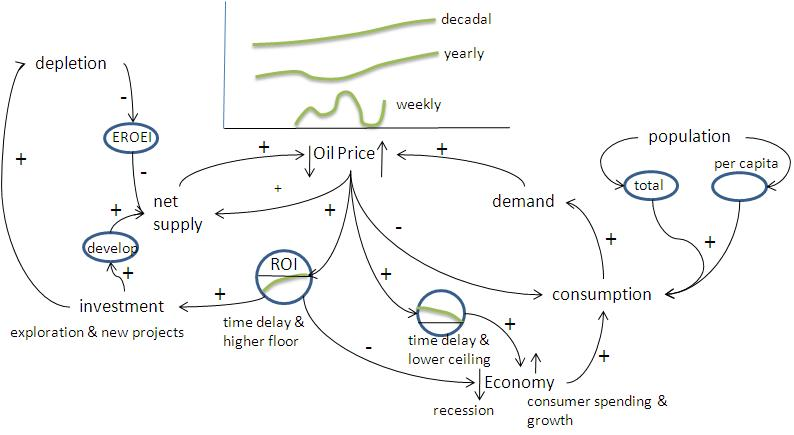

The Price of Oil: Not as Simple as You Think

Wednesday, August 4, 2010

Gulf of Mexico Dead Zone 2010

The previous post showed a map of dead zones around the world. Nancy Rabalais, Executive Director of Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium and Chief Scientist aboard the research vessel Pelican, has released an update on the Gulf of Mexico Dead Zone -- noting that it is one of the largest ever. Some pertinent quotes follow:

The area of hypoxia, or low oxygen, in the northern Gulf of Mexico west of the Mississippi River delta covered 20,000 square kilometers (7,722 square miles) of the bottom and extended far into Texas waters. The relative size is almost that of Massachusetts. The critical value that defines hypoxia is 2 mg/L, or ppm, because trawlers cannot catch fish or shrimp on the bottom when oxygen falls lower.

This summer’s hypoxic zone (“dead zone”) is one of the largest measured since the team of researchers from Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium and Louisiana State University began routine mapping in 1985. Dr. Nancy Rabalais, executive director of LUMCON and chief scientist aboard the research vessel Pelican, was unsure what would be found because of recent weather, but an earlier cruise by a NOAA fisheries team found hypoxia off the Galveston, Texas area. She commented “This is the largest such area off the upper Texas coast that we have found since we began this work in 1985.” She commented that “The total area probably would have been the largest if we had had enough time to completely map the western part.”

LSU’s Dr. R. Eugene Turner had predicted that this year’s zone would be 19,141 to 21,941 square kilometers, (average 20,140 square kilometers or 7,776 square miles), based on the amount of nitrate-nitrogen loaded into the Gulf in May. “The size of the hypoxic zone and nitrogen loading from the river is an unambiguous relationship,” said Turner. “We need to act on that information.”

The size of the summer’s hypoxic zone is important as a benchmark against which progress in nutrient reductions in the Mississippi River system can be measured. The Mississippi River/Gulf of Mexico Nutrient Management Task Force supports the goal of reducing the size of the hypoxic zone to less than 5,000 square kilometers, or 1,900 square miles, which will require substantial reductions in nitrogen and phosphorus reaching the Gulf. Including this summer’s area estimate, the 5-year average of 19,668 square kilometers (7,594 square miles) is far short of where water quality managers want to be by 2015.

For more information: http://www.gulfhypoxia.net

Monday, August 2, 2010

Half the Oxygen We Breathe

from the press release:

The findings contribute to a growing body of scientific evidence indicating that global warming is altering the fundamentals of marine ecosystems. Says co-author Marlon Lewis, "Climate-driven phytoplankton declines are another important dimension of global change in the oceans, which are already stressed by the effects of fishing and pollution. Better observational tools and scientific understanding are needed to enable accurate forecasts of the future health of the ocean." Explains co-author Boris Worm, "Phytoplankton are a critical part of our planetary life support system. They produce half of the oxygen we breathe, draw down surface CO2, and ultimately support all of our fisheries. An ocean with less phytoplankton will function differently, and this has to be accounted for in our management efforts."

Dead zones and more good news :+( about the ocean

Following up on the previous post, here is a post from Garry Peterson of Resilience Science.

===============================================================

I’ve published several links to global maps of coastal hypoxia. Now, NASA has produced a new map of global hypoxic zones, based on Diaz and Rosenberg’s . Spreading Dead Zones and Consequences for Marine Ecosystems. in Science, 321(5891), 926-929. NASA’s EOS Image of the Day writes on Aquatic Dead Zones.

Red circles on this map show the location and size of many of our planet’s dead zones. Black dots show where dead zones have been observed, but their size is unknown.

It’s no coincidence that dead zones occur downriver of places where human population density is high (darkest brown). Some of the fertilizer we apply to crops is washed into streams and rivers. Fertilizer-laden runoff triggers explosive planktonic algae growth in coastal areas. The algae die and rain down into deep waters, where their remains are like fertilizer for microbes. The microbes decompose the organic matter, using up the oxygen. Mass killing of fish and other sea life often results.

Sunday, August 1, 2010

Oysters without even a half-shell

Interesting article in the Seattle Times examining the fact that billions of Pacific oyster larvae have died and oysters in the wild on Washington's coast haven't reproduced in six seasons. Scientists suspect ocean-chemistry changes linked to fossil-fuel emissions, the oceans are becoming more acidic (which the article calls 'corrosive'), are killing the juvenile shellfish. The article goes on to list a variety of changes being observed and suggests an 'upheaval,' perhaps akin to a regime shift, may be underway.

Signs environmental upheaval may be under way:

Sea snails: Tiny sea snails called pteropods, which make up 60 percent of the diet for Alaska's juvenile pink salmon, essentially dissolve in corrosive waters. Some microscopic plankton also are important fish food, and some are highly susceptible to corrosive water.

Clownfish: Scientists in Australia found that larval clownfish and damselfish exposed to corrosive waters tended to follow the scent of predators and were five to nine times more likely to die.

Killer whales: The ocean will absorb less background noise — in effect, become noisier — when pH levels drop by even small amounts. Research hasn't been done to detail what impact, if any, that might have on marine mammals such as orcas that rely on biosonar.

Giant squid: Scientists say the giant squid, also known as the Humboldt squid, typically found at depths of 660 to 2,300 feet, grow lethargic when subjected to acidified waters.

Sea urchins: Purple sea-urchin larvae exposed to acidifying waters were smaller, "stumpier" in shape and had less skeletal mass.

Oysters: Wild Pacific oysters have not reproduced in Willapa Bay for six years. Scientists suspect acidifying water, rising from the deep in coastal "upwelling" events, is helping wipe out juvenile oysters before they can grow.

Seagrass: All five species of seagrass that have been studied were found to thrive in increasingly corrosive waters.