Photos by Amy Stein

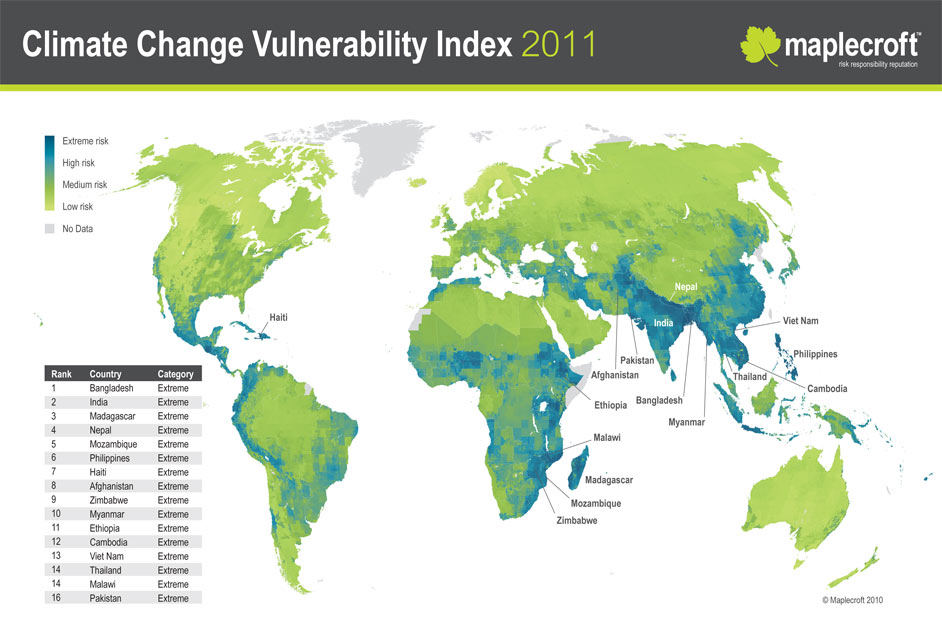

The results, summarized by the accompanying map, rank countries from extreme to low risk. A number of countries projected to be major economies of the future are among those with either extreme (Bangladesh, India, Philippines, Vietnam and Pakistan) or very high (China, Brazil, Japan) levels of risk. The Guardian summarized the report as follows:

The results, summarized by the accompanying map, rank countries from extreme to low risk. A number of countries projected to be major economies of the future are among those with either extreme (Bangladesh, India, Philippines, Vietnam and Pakistan) or very high (China, Brazil, Japan) levels of risk. The Guardian summarized the report as follows:According to Maplecroft, the countries facing the greatest risks are characterised by high levels of poverty, dense populations, exposure to climate-related events and reliance on flood- and drought-prone agricultural land.

Bangladesh ticks most of these boxes and the report warns that rising climate risks could hit foreign investment into the country, undermining the driving force behind economic growth of 88 per cent between 2000 and 2008.

Similarly, the report warned that India's massive population and increasing demand for scarce resources made it particularly sensitive to climate change.

Other Asian countries attracting high levels of foreign investment such as the Philippines, Vietnam and Pakistan were also classified as facing 'extreme risk' from climate change, while industrial giants China, Brazil and Japan are listed as 'high risk'.

"This means organisations with operations or assets in these countries will become more exposed to associated risks, such as climate-related natural disasters, resource security and conflict," said Dr Matthew Bunce, principal environmental analyst at Maplecroft. "Understanding climate vulnerability will help companies make their investments more resilient to unexpected change."

Some states were not listed because of a lack of data, including North Korea and small island states such as the Maldives that are vulnerable to rising sea l evels.

Wealthy European nations made up the majority of low risk countries, with Norway, Finland, Iceland, Ireland, Sweden and Denmark deemed to face the lowest risk of climate-related disruption.

However, Russia, USA, Germany, France and the UK were all rated as 'medium risk' countries.

The software correctly classified me as male and, not surprisingly, recognized the tone as academic. As someone thinks of themselves as young at heart (I have a passion for indie music and have frequently been the oldest, by several decades, at numerous concerts I've attended), it was a bit of a shock to be identified as somewhere in the 66-100 range. Got to work on that. Perhaps the June Cleaver image in the previous post will ..... oops, no ... that was a 60's show and the software only analyzes text. Anyway, given the rather dour topics that the blog covers, it was nice to find the mood remains happy!

The software correctly classified me as male and, not surprisingly, recognized the tone as academic. As someone thinks of themselves as young at heart (I have a passion for indie music and have frequently been the oldest, by several decades, at numerous concerts I've attended), it was a bit of a shock to be identified as somewhere in the 66-100 range. Got to work on that. Perhaps the June Cleaver image in the previous post will ..... oops, no ... that was a 60's show and the software only analyzes text. Anyway, given the rather dour topics that the blog covers, it was nice to find the mood remains happy!

According to the classic academic narrative of political evolution, post-ice age complexity — defined as increasing levels of social hierarchy — evolved slowly but surely, with mechanical predictability. First came egalitarian bands of closely-related people; then came larger but still-egalitarian tribes, with only informal leadership; these clustered into chiefdoms, with hereditary leaders; chiefdoms united into states, with bureaucracies and administrative offices.

To some scholars, however, this narrative is deterministic. They say that political evolution doesn’t proceed neatly from lower to higher complexity, but proceeds in bursts. To them, tribes, chiefdoms and states all represent distinct evolutionary trajectories rather than stages of a single progression. The critics also say that the tendency of societies to move from higher to lower complexity has been underestimated.

Here is the article's abstract:

There is disagreement about whether human political evolution has proceeded through a sequence of incremental increases in complexity, or whether larger, non-sequential increases have occurred. The extent to which societies have decreased in complexity is also unclear. These debates have continued largely in the absence of rigorous, quantitative tests. We evaluated six competing models of political evolution in Austronesian-speaking societies using phylogenetic methods. Here we show that in the best-fitting model political complexity rises and falls in a sequence of small steps. This is closely followed by another model in which increases are sequential but decreases can be either sequential or in bigger drops. The results indicate that large, non-sequential jumps in political complexity have not occurred during the evolutionary history of these societies. This suggests that, despite the numerous contingent pathways of human history, there are regularities in cultural evolution that can be detected using computational phylogenetic methods.

While this is more speculation than evidence based conclusion, translating these findings into a panarchy framework highlights some interesting possibilities. Specifically, it seems that some of the transitions (e.g., from simple to complex chiefdom) would most likely be the product of adaptive cycle processes. Others, however (e.g., from complex chiefdom to state), seem intuitively to involve the emergence of processes operating at a larger scale (similar to the problem of going from nation-state to global governance). In other words, to involve the emergence of a new and separate adaptive cycle that operates at a larger scale. If this is the case, this would also make sense of the asymmetric nature of the process whereby development occurs in a path (with each level in the controlling panarchy necessary for the emergence of the next) but collapse can be more dramatic (as processes of cross-scale interaction cascade down through the panarchical levels).

While this is more speculation than evidence based conclusion, translating these findings into a panarchy framework highlights some interesting possibilities. Specifically, it seems that some of the transitions (e.g., from simple to complex chiefdom) would most likely be the product of adaptive cycle processes. Others, however (e.g., from complex chiefdom to state), seem intuitively to involve the emergence of processes operating at a larger scale (similar to the problem of going from nation-state to global governance). In other words, to involve the emergence of a new and separate adaptive cycle that operates at a larger scale. If this is the case, this would also make sense of the asymmetric nature of the process whereby development occurs in a path (with each level in the controlling panarchy necessary for the emergence of the next) but collapse can be more dramatic (as processes of cross-scale interaction cascade down through the panarchical levels).

In a strange convergence, the deaths of two iconic contributors to global visual culture were announced yesterday.

In a strange convergence, the deaths of two iconic contributors to global visual culture were announced yesterday. At the other end of the spectrum, is eccentric mathmatecian Bernoit Mandelbrot. In contrast to Billingsley, whose visual image became synonymous with her iconic character, few would recognize a photo of Mandelbrot. They would, however, recognize images based on the fractal geometry he described. And, of more direct relevance to this blog, the fractal notion of self similarity is at the core of Andrew Abbott's brilliant analysis of sociological theory -- The Chaos of Disciplines. Mandelbrot's obituary is here.

At the other end of the spectrum, is eccentric mathmatecian Bernoit Mandelbrot. In contrast to Billingsley, whose visual image became synonymous with her iconic character, few would recognize a photo of Mandelbrot. They would, however, recognize images based on the fractal geometry he described. And, of more direct relevance to this blog, the fractal notion of self similarity is at the core of Andrew Abbott's brilliant analysis of sociological theory -- The Chaos of Disciplines. Mandelbrot's obituary is here.

Adaptation, resilience, vulnerability, and coping with change in social-ecological systems Governance, polycentricity, markets, and multilevel challenges Analyzing and framing resilient development, resilient resources and security

One of the most detailed (and depressing) accounts of this failure can be found in an article by Ryan Lizza, As the World Burns: How the Senate and the White House missed their best chance to deal with climate change in the current issue of the New Yorker. The article describes the factors that initially brought together an unusual coalition of Senators (Republican Lindsey Graham, Independent Joe Lieberman, and Democrat John Kerry) to draft a Senate energy and climate change bill and a second set of factors that blew apart the coalition before the bill was brought to a vote.

One of the most detailed (and depressing) accounts of this failure can be found in an article by Ryan Lizza, As the World Burns: How the Senate and the White House missed their best chance to deal with climate change in the current issue of the New Yorker. The article describes the factors that initially brought together an unusual coalition of Senators (Republican Lindsey Graham, Independent Joe Lieberman, and Democrat John Kerry) to draft a Senate energy and climate change bill and a second set of factors that blew apart the coalition before the bill was brought to a vote. A TV network acting as the political enforcer of the Republican Party: Lizza: “Back in Washington, Graham warned Lieberman and Kerry that they needed to get as far as they could in negotiating the bill ‘before Fox News got wind of the fact that this was a serious process,’ one of the people involved in the negotiations said. ‘He would say: The second they focus on us, it’s gonna be all cap-and-tax all the time, and it’s gonna become just a disaster for me on the airwaves. We have to move this along as quickly as possible.’ ”

Special interests buying policy: Lizza: “Then Newt Gingrich’s group, American Solutions, whose largest donors include coal and electric-utility interests, began targeting Graham with a flurry of online articles about the ‘Kerry-Graham-Lieberman gas tax bill.’ ”

Politicians who put their interests before the country’s: Lizza: “Then, suddenly, there was a new problem: Harry Reid, the Senate majority leader, said that he wanted to pass immigration reform before the climate-change bill. It was a cynical ploy. Everyone in the Senate knew that there was no immigration bill. Reid was in a tough re-election, and immigration activists, influential in his home state of Nevada, were pressuring him.”

A political system that cannot manage multiple policy shifts at once — even though it needs to: Lizza: Obama aide Jay Heimbach attended meetings with the three sponsoring senators, “but almost never expressed a policy preference or revealed White House thinking. ‘It’s a drum circle,’ one Senate aide lamented. ‘They come by: How are you feeling? Where do you think the votes are? What do you think we should do? It’s never: Here’s the plan, here’s what we’re doing.’ Said one Obama adviser, explaining the president’s difficulty in motivating Congressional Democrats on energy: ‘The horse has been ridden hard this year and just wants to go back to the barn.’ ”

I just have one thing to add: We need to do better. ...

Several years ago, while at the Environment Section presentations at the ASA meetings in San Francisco, I had the pleasure of meeting Jason Moore. At that point he was a graduate student at UC-Berkley. The paper he presented (later published as "Silver, Ecology, and the Origins of the Modern World, 1450-1640") was, by far, the most interesting one at the conference.

Several years ago, while at the Environment Section presentations at the ASA meetings in San Francisco, I had the pleasure of meeting Jason Moore. At that point he was a graduate student at UC-Berkley. The paper he presented (later published as "Silver, Ecology, and the Origins of the Modern World, 1450-1640") was, by far, the most interesting one at the conference.Does the present socio-ecological impasse – captured in popular discussions of the ‘end’ of cheap food and cheap oil – represent the latest in a long history of limits and crises that have been transcended by capital, or have we arrived at an epochal turning point in the relation of capital, capitalism and agricultural revolution? For the better part of six centuries, the relation between world capitalism and agriculture has been a remarkable one. Every great wave of capitalist development has been paved with ‘cheap’ food. Beginning in the long sixteenth century, capitalist agencies pioneered successive agricultural revolutions, yielding a series of extraordinary expansions of the food surplus. This paper engages the crisis of neoliberalism today, and asks: Is another agricultural revolution, comparable to those we have known in the history of capitalism, possible? Does the present conjuncture represent a developmental crisis of capitalism that can be resolved by establishing new agro-ecological conditions for another long wave of accumulation, or are we now witnessing an epochal crisis of capitalism? These divergent possibilities are explored from a perspective that views capitalism as ‘world-ecology’, joining together the accumulation of capital and the production of nature in dialectical unity.